Paul Singer says this is the next “Big Short”

By Rupert Hargreaves

When speaking at the recent Grant’s Spring Conference at the Plaza in New York earlier this year, Paul Singertalked about his ideas for the next “Big Short”. In Elliott’s first quarter letter to investors, a copy of which was reviewed by ValueWalk, Singer goes into more detail on how he sees the short playing out.

In reference to Michael Lewis’ book, “The Big Short”, which covers the 2005-2007 credit bubble, Singer has named his new trade “The Bigger Short”. He states:

“Today, six and a half year after the collapse of Lehman, there is a Bigger Short cooking. That Bigger Short is long-term claims on paper money, i.e., bonds.”Singer continues:

“History shows that it is fiendishly difficult to preserve the value of money which is backed by nothing but promises, because it is so tempting for rulers to debase their currency when they think it will help them repay their debts. The long-term preservation of the real value (i.e., the purchasing power) of fiat money and bonds is obviously of little or no importance to today’s creators of money…Yet, the current prices of bonds are at all-time highs, and thus yields are at record lows, because the central banks are buying bonds with trillions of dollars of newly printed money”Singer accuses the central banks of hampering the global economic recovery by continuing to print money despite the fact that the financial crisis ended nearly five years ago. Moreover, Singer observes that the definition of money has become blurred since the 1970s, with few market participants, or even Fed Chair Janet Yellen able to state that they fully understand what money and debt are.

“The Global Financial Crisis of 2008…was not an accident, but rather a natural consequence of connectivity and excessive leverage. Because policy makers have not fixed what went wrong in the GFC, and because their solution has been to pile even more debt on top of the already-sky-high indebtedness…we believe that a new, highly impactful financial crisis is likely.”

Bigger Short - Timing the collapse

The difficult part of trying to forecast any crisis is timing the collapse. Early moves in the last crisis, notably Michael Burry, faced an investor revolt when they started betting against the market as early as 2005.When trying to assess a complex matter like this, Elliott finds it useful to analyze complicated matters “and then transition, clearly and openly, to opinion.” Over the past 40 years there has been a huge shift in the working patterns across developed nations, productivity has fallen and manufacturing jobs have been moved overseas. The full force of these effects Singer notes hit the developed world during the last financial crisis but policy makes have failed to react:

“Unfortunately, the political leadership of the developed world has been very slow to recognize these major forces that are acting on their economies, and very few effective new policies, or changes in existing policies, have been put in place to counteract these negative trends.”Serious reform has proved to be politically unpalatable, and debts have continued to mount. Political leaders in the developed world have not moved in any meaningful way toward policies that would stimulate economic growth based on the new normal as it were. Stimulus efforts have largely been devoted to supporting relatively inefficient public-sector jobs and government spending. Further, the tone of policymakers populist and cranky toward capitalists, finance, and financiers. As Singer notes:

“Not a welcoming environment for job creation, in a world in which capital will go where it is welcome.”Elliott’s view is that central bankers have chosen, and doubled down on, a palliative (super-easy money and QE), policy which is unprecedented and extreme, and whose ultimate effects are unknowable. Somehow, the primary goal of both central banks and policy makes has become to generate more inflation, and bondholders have ignored this fact. The goal of generating more inflation is aimed at reducing the value of their capital. Moreover, the financial world has become used to slow-and-steady central bank movements.

“We call to your attention the hand-wringing and agonizing now underway about raising U.S. policy rates by 25, 50 or 75 basis points over the next few months. Imagine the caterwauling in global financial markets if inflation surprises everyone on the upside and the right policy rate should be 2%, 4% or higher. Given the fragility of the financial system and its still-extreme leverage, even a few points of inflation and a few hundred basis points of increase in medium- and long-term interest rates could cause a renewed financial crisis.”

The Bigger Short: A poor deal

Singer goes on to discuss the poor

deal the bondholders of today are getting. At current interest rates on

long-term bonds, if there is any level of inflation over the next

10 to 30 years, investors who buy or hold bonds at today’s prices and

rates will have made a terrible mistake. If inflation takes off, they

are truly in trouble.

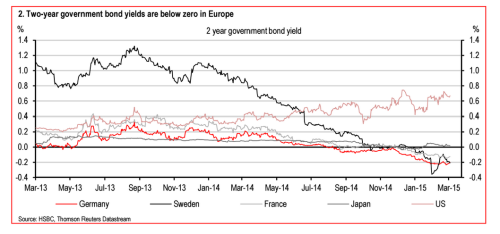

The numbers Singer presents to back up his “Bigger Short” case are pretty staggering. At the time of writing, the German 30-year bond with a 2.5% coupon traded at 153.4, giving a yield to maturity of 0.62%. However, if the market yield for 30-year paper rises to 1% the bond price will decline by 8.6%, which, when compared to the starting yield of 0.62% is a concerning loss. But that’s not all, if the yield on the 30-year paper were to increase to 2% – a level seen only several months ago – the bond price would fall by 27%. A 3% yield would result in a capital loss of 41% and a 4% yield would cause a loss of 51.5% to a price of 73.5.

“This risk-reward profile is pure madness. Imagine any holder taking the risk, for a maximum yield of 0.62% for 30 years, of losing 40% or 50% of capital if interest rates simply revert to historically normal levels with a small amount of inflation, to say nothing of serious inflation or hyperinflation.”Bonds are no longer a low-risk asset but money continues to flow into the sector, pushed by central bank policies and public sector purchases.

Singer concludes:

“A good or great trade is not created by just the prospect of a big move in a direction. The ability of investors to engage in a superior risk/reward profile, and to finesse the question of when the expected move will occur, is what separates “just-ok” trades from great trades. It is the extreme overpricing of bonds, and the universal confidence (unjustified, in our opinion) of investors in central banks and in the current mix of perceptions about what is safe and what is not, that makes the Bigger Short into possibly a great trade.”