How does the traditional collector of ancients judge the beauty of an ancient coin?

How does NGC judge the beauty of an ancient coin?

How do you judge the beauty of an ancient coin?

Different questions. Because everyone's aesthetic is - and should be - different.

Yet there are certainly aspects to the traditional view of the beauty of an ancient coin that can be objectively gauged.

Some of these will be reflected in NGC grades, some will not. Outside of condition, which is NGC's obvious strong suit, here some other facets I feel are good to consider when developing your own aesthetic.

These are - in the order of importance - in my opinion:

1)

Skill of the die carver (celetor). This does not count in the NGC grade - or in the "fine style" designation - unless the coin's coindition is attractive in a global way in the opinion of the grader.

Yet a skillfully engraved coin will usually appeal to many collectors. It is not difficult to

recognize a skillfully engraved coin. In the case of a portrait, you feel it has been modeled on an actual person.

In case of a mythical tableau. you feel the human emotion associated to the myth: the Grandeur of Zeus, the fierceness of the Winged Lion etc.

What can be more controversial is the difference between a routinely well crafted coin and a true masterpiece of art.

The masterpiece captures and conveys something of the human condition.

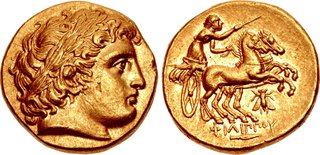

Generally this is to be found in a well executed portrait that conveys insight into who the person was: For example this fine style tetradrachm of Lysimachus has a truly a stunning Alexander portrait, wherein we can experience the combination of will, focus, fierceness and noble beauty that so inspired his troops:

Is can also be found in a composition that conveys exactly what is so compelling about a particular Myth.' This Odysseus sacrifice scene, captures the drama of the moment before death, the ultimate sacrifice.

The masterpiece of coinage will afford the collector great pleasure with every viewing regardless of whether it it noted on the holder. For example this masterpiece by signed by the Delta Artist, lacks the fine style designation on the holder:

Even a routinely well crafted coin will appeal to the eye in a far more satisfying way than a perfectly preserved coin executed by a aesthetic dunce. And many NGC fine style coins are only routinely well crafted

NGC "fine style" yet only routinely well crafted.

2)

Die State/ Metal Quality. A coin stuck from fresh dies on good metal is also something not reflected in the NGC grade, yet traditionally it one of things most prized by collectors because there is little that appeals to the eye more than a fresh image on good metal. There is nothing more depressing than a Choice Mints State, coin that is marred by badly rusted or blundered or worn dies. Just as even a smattering of die rust can destroy the aesthetic appeal of an otherwise beautiful coin - depending on where it occurs - and how distracting.

For example here is an NGC CH AU 4/5 5/5 "Fine style" gold Syracuse 50 litrae with both die rust and a badly worn die in the chin area - that is really hideous to the eye. It has been engraved by a skilled die cutter - but the die state is atrocious.

How to tell the die state? For one thing - absence of die rust. For another: Deep definition of line. On a fresh die the image pops off the flan. This is obviously more subjective, and often difficult to capture in a photo. But you'll know it when you see it. To old time collectors of CNG coins, the designation "Struck from fresh dies" was something that always elicited excitement - and a premium bid.

3)

Strike and Centering. These are issues that are certainly reflected both in the strike grade and the Star designation at NGC. And there is no doubt something satisfying in a well centered coin. However, it must be noted that many ancient coins have an obverse of prime aesthetic importance and a reverse that serves more to impart information - civic ethnic, titles and affiliations, or, in the case of archaic coins, simple punches. If the reverse punch is off center it may affect the strike grade - but so what? Who buys an archaic coin to contemplate the punch? And who buys an Alexander portrait to admire the placement of the chariot on the reverse? Some people do, but more often the portrait is most important.

Many small striking problems - like die shifts that can only be seen at the edges, or perhaps a slight doubling of horse hooves on the reverse - may be recorded on the holder but, really, again, do these problems interfere in any way with the aesthetics of the coin?

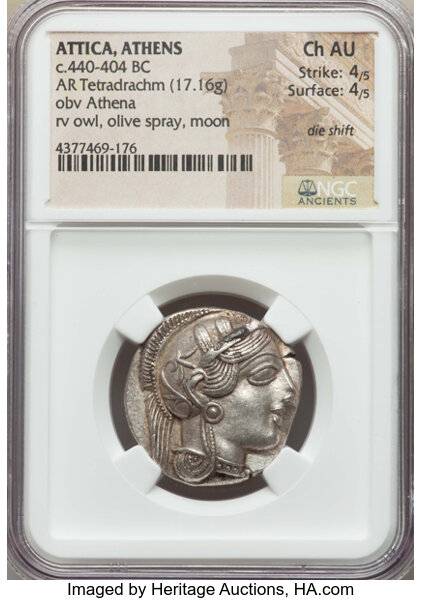

For example this Athenian tetradrachm, suffers from a die shift that in no way interferes with

the lovely style. (not noted) . But it results in reduced strike grade and a notation on the holder - as well, quite possibly, the omission of the fine style designation. Yet it is a premium example of this coin, and far more beautiful than many CH MS examples.

At the same time most collectors rightfully shun coins where parts of the design are completely off the flan.

4)

Toning. Again, of minor importance to the NGC designations, but something that obviously has a great effect on the eye appeal of a coin. A beautifully toned coin - especially in silver, can add greatly to one's aesthetic enjoyment. For example this beautifully toned didrachm of Calabria, rightfully has received both "fine style" and star designations. It is also struck, quite clearly from fresh dies.

6)

Surface - I consider minor marks on the surface of a coin to be the least important of aesthetic factors. Obviously when buying a portrait, one doesn't like to see scuffs across the face. But does a scuff in the field of an otherwise beautiful portrait really matter? It may drastically reduce the surface grade, and it may also be noted on the holder - but it may also only be noticeable if one tilts the coin at an angle and studies the field. What is the point of studying the field when an artistically masterful image is popping off the flan, just begging to be appreciated?

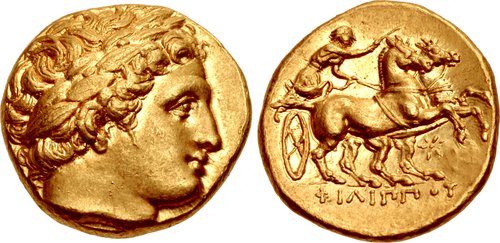

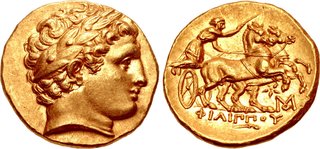

For example this attractive stater has scuffs (on the neck) noted on the holder - yet they certainly in no way distract from the very well crafted (yet not exceptional) portrait. (again, not noted.)

The way in which the coin has been cleaned may drastically reduce a surface grade - yet nearly all ancient coins have been cleaned - just as nearly all old master paintings have been cleaned. Slight differences in degree to which they'd been cleaned matter greatly to graders - but they hardly affect the aesthetics of the piece unless the cleaning has been materially botched.

COMMON SENSE: As in everything, use common sense in the aesthetic appreciation of a coin. Trust your eye. If problems are noted on the holder that you can't see, perhaps they're not of any material concern. If a coin is noted as fine style and you don't like the style - then it's not fine style to you. If the notation is lacking and you see a masterpiece, perhaps you should jump at the chance to get an underappreciated masterpiece.

This one, for example doesn't do much for me. It looks more like a chicken than a Siren.

This one, for example doesn't do much for me. It looks more like a chicken than a Siren.

Some, like this coin, endeavor to evoke an entire mythological story To quote the catalogers at CNG : This rare type depicts the legend of the omphalos (navel) stone, which marked the sacred precinct of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi as the physical center of the earth. According to tradition, two eagles, which had been released by Zeus, one flying from the east, and the other from the west, met exactly at the site of Apollo’s sanctuary.

Some, like this coin, endeavor to evoke an entire mythological story To quote the catalogers at CNG : This rare type depicts the legend of the omphalos (navel) stone, which marked the sacred precinct of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi as the physical center of the earth. According to tradition, two eagles, which had been released by Zeus, one flying from the east, and the other from the west, met exactly at the site of Apollo’s sanctuary.

NGC "fine style" yet only routinely well crafted.

NGC "fine style" yet only routinely well crafted.